When Valuations Matter

Stock valuations have remained high for a few years now, and yet stocks have mostly shrugged off those concerns. The price of the S&P 500 is up 34.3% over the past year and 95.8% over the past five years.

Stock valuations are a measurement of the price of a stock in comparison to some intrinsic value. Traditionally, valuations hold price in the numerator and intrinsic value in the denominator.

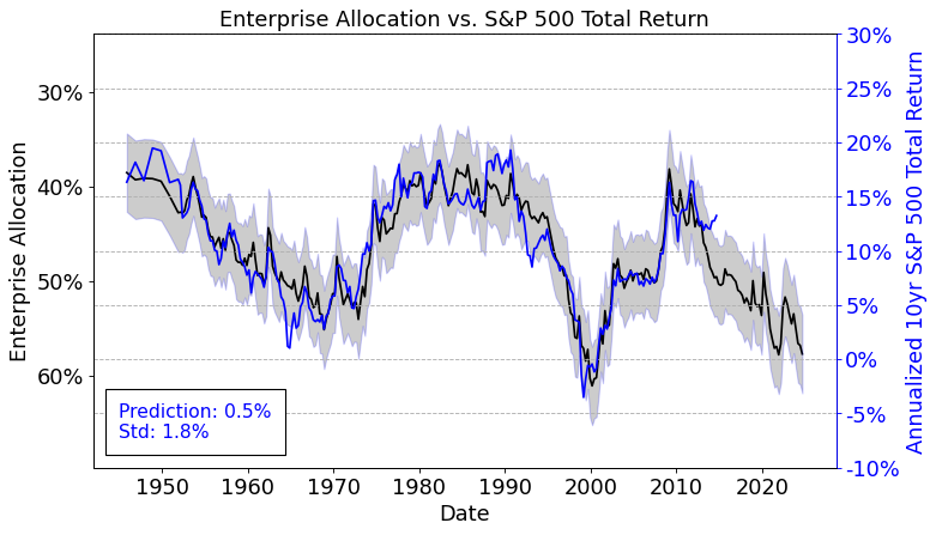

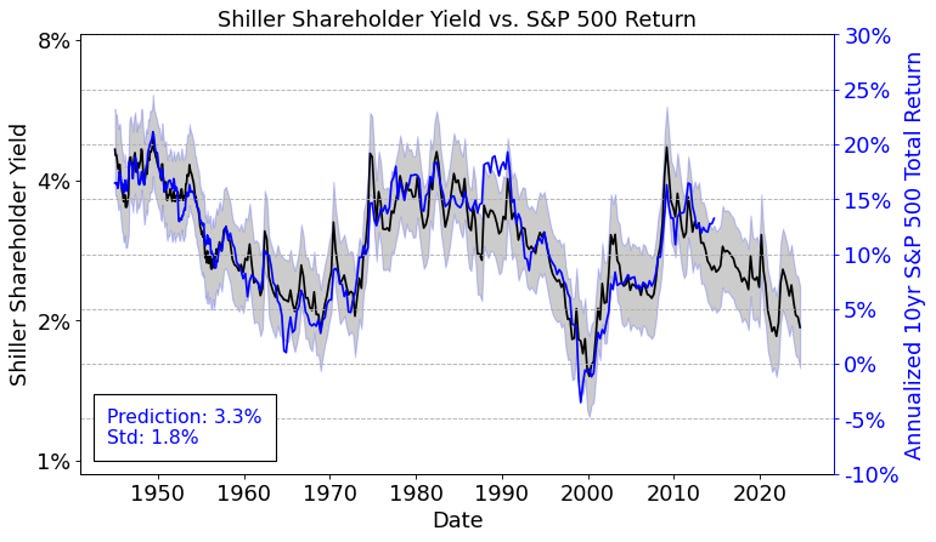

My two favorite valuation metrics to measure the overall stock market and predict forward returns are included below. “Enterprise Allocation” is the ratio of equities and corporate debt to all economic assets. “Shiller Shareholder Yield” is the ratio of shareholder payments via dividends and stock buybacks (specifically, the 10-year average) to equities. You might note that Shiller Shareholder Yield is inverted in comparison to traditional valuation metrics.

As is evident from the charts above and was partially explored in my June letter, valuations take a long time to affect returns. Economic outcomes are much more powerful drivers of short-term returns.

But that then begs the question, when are valuations instructive?

I suggested in that June letter that “low returns aren’t realized until the economy experiences a period of low growth.” To further demonstrate that conclusion, I collected a sample of recessions, peak valuations prior to the recession, stock market highs before the recession, and stock market lows during or after the recession.

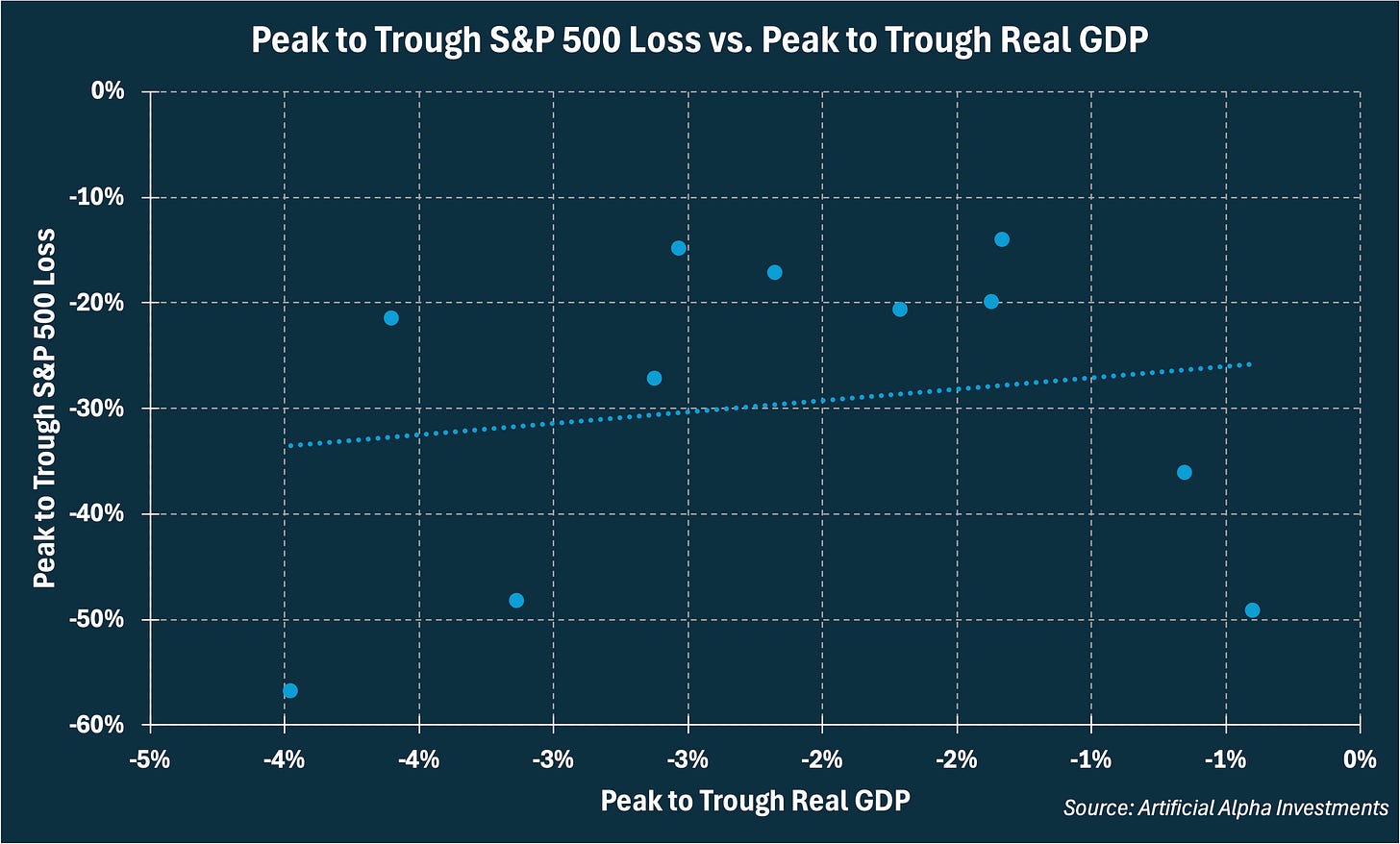

First, let me address a common misunderstanding that the severity of a recession determines the severity of stock market losses. There is almost no correlation between Real GDP drawdowns and S&P 500 drawdowns.

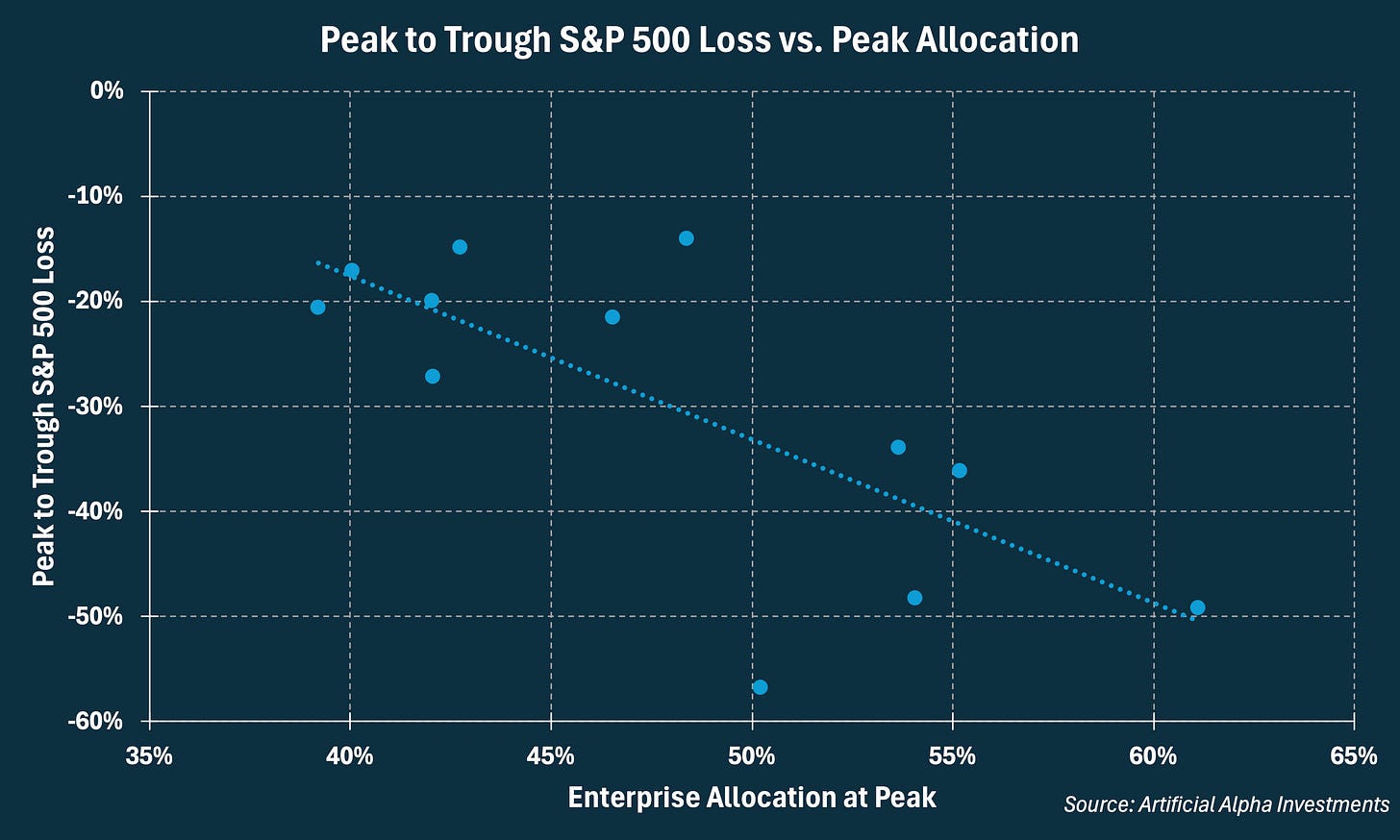

Instead, notice how strongly S&P 500 losses are related to valuations (Enterprise Allocation in this case). Valuations have historically determined the difference between 50% expected losses and 17% expected losses during a recession.

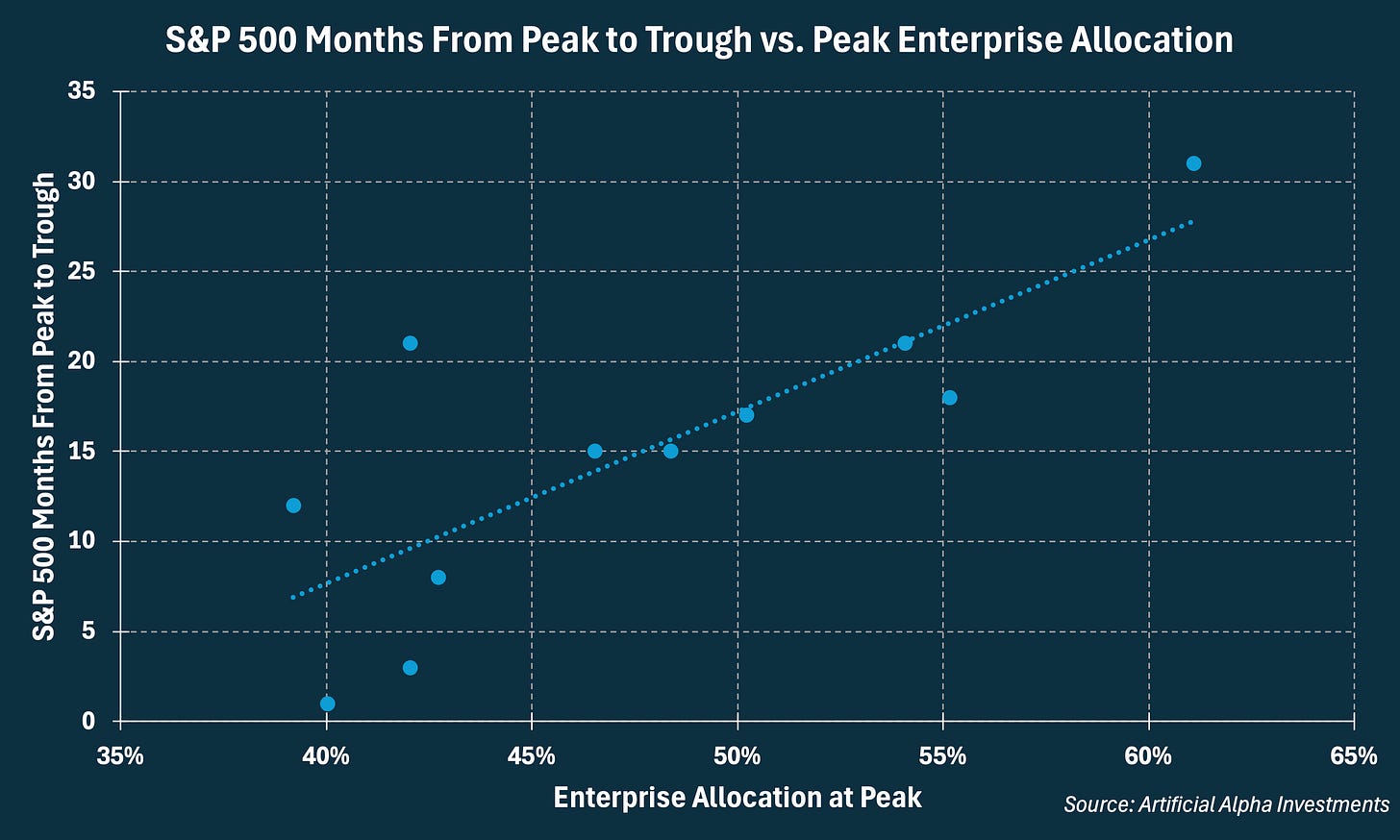

In addition to the severity of losses, valuations also inform us to how many months the stock market drawdown will last. This chart excludes the 2020 recession because it wasn’t a normal business cycle slowdown.

Currently, stocks have an Enterprise Allocation of 58%. Given a recession, we might expect 45% losses over 25 months.

Some of my recent letters have argued for stock market diversification away from the S&P 500. This preference is partially due to more reasonable valuations in other parts of the stock market. I believe a recession would have a lighter impact on small-caps, mid-caps, and other neglected groups.

Stock Market Concentration (pt. 2)

Even if investors don’t diversify away from the S&P 500, many long-term investors (10+ years) should be able to look past these risks. This letter is to prepare long-term investors for a recession that, although unpredictable, could require us to endure a particularly bumpy road.