A History of Financial Manias

I’m hoping this accumulation of ideas and comparisons will evoke both a qualitative and quantitative characterization of today’s financial landscape. I’m not sure you should act with any haste on these ideas.

First, because by all indications we have a robust economic environment coming into 2025. This analysis does not outmuscle a strong economy. Please read Short-Term Drivers and When Valuations Matter for a dissection of economic growth and valuations.

And second, because I’ve shared these thoughts with friends and colleagues and been met with an incredibly wide array of responses. I think each response was appropriate, considering each person’s unique preferences and timeframes.

With that said, today’s financial environment is too much of an outlier to not share my interpretation on where we stand. Here’s a synthesis of some obsessive research on technology cycles, financial manias, and mispriced monopolies.

America’s Technological Eras

The following eras all exhibited the same financial, economic, and social characteristics. I might suggest slightly different dates than social historians because of my added attention to financial conditions. The first resemblance among these eras are their technology origins.

The Railway Mania (1840-1860) began in the U.K. in the 1840s and quickly spread to America. Before the railways, non-bank businesses were not widely financed in public U.S. markets. After the railways, technological innovation flourished and new sectors of the economy were born.

The Gilded Age (1873-1906) was a period of great economic innovation, spurred by the railroads and resulting in factories, mining, energy, and finance. More than half the population was freed from agrarian lifestyles for the first time in history.

The Roaring Twenties (1920-1929) are best known for their societal change, but supporting all that social integration were major technological breakthroughs in automobiles, electricity, radio, and telephones.

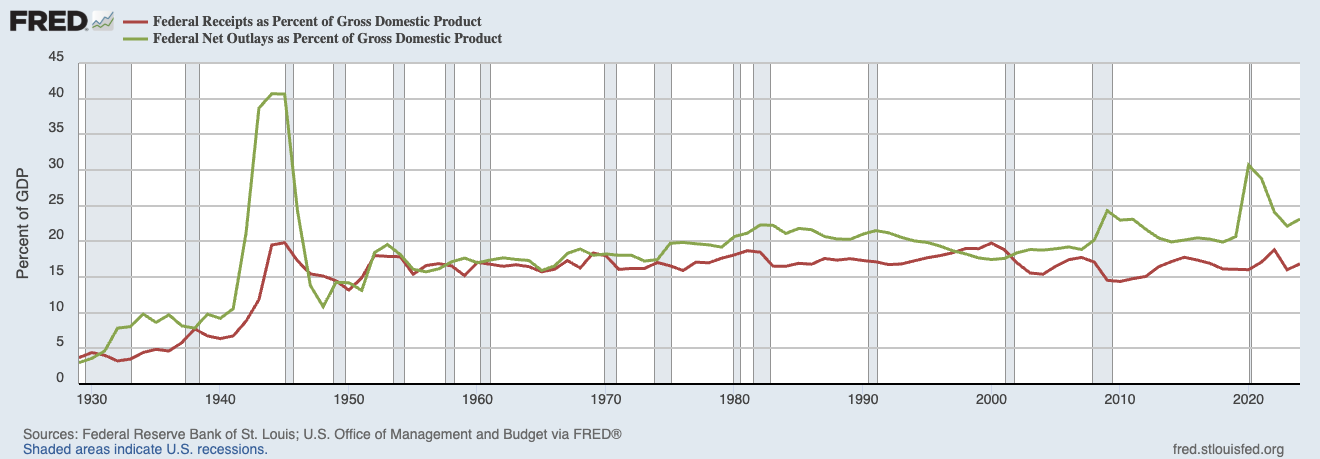

The New Deal Era (1932-1940) might seem unique on this list but I would argue that these government transformations should be remembered as giant innovations. Federal taxation and spending increased dramatically.

The Cold War Era (1949-1973) saw immense progress among technologies that serve the government. U.S. atomic bomb production peaked in 1965 and we landed on the moon in 1969. I might point towards dollarization and the Federal Reserve’s rise to power first, but that’s an esoteric choice.

The Dot-com Era (1983-2000) began with the invention of the internet in 1983, which proceeded to connect everything and everyone like never before.

The iPhone Era (2009-???), as I’ll call it for now, began at the conclusion of the Great Financial Crisis when handheld devices augmented our consumption of almost all information.

Tech-Fueled Monopolies

Monopolies, oftentimes earned through technological innovation, came to dominate the financial landscape by the end of each era. Here are some limited examples.

Railway Mania (1840-1860): Railroads like Pennsylvania Railroad were merging all over the country. The government subsidized new construction and competition but did a poor job of suppressing monopolies in the 1860s.

Gilded Age (1873-1906): America’s monopoly problem once again came to a head in 1904 as Standard Oil controlled “91% of oil refinement and 85% of final sales in the United States.” This time, new antitrust laws finally split up the old railroads and broke Standard Oil into 39 companies.

Roaring Twenties (1920-1929): Ford and U.S. Steel had little threatening competition. And AT&T benefited from a government-enforced monopoly called the Bell System that let them capture “over 60% share of national users of phones.”

New Deal Era (1932-1940): The government did a poor job of suppressing monopolies during the Great Depression, so we replayed all the same hits from the Roaring Twenties.

Cold War Era (1949-1973): The Cold War resulted in less outright monopolies (unless you account for the federal government’s new stranglehold on power), but that doesn’t mean the market wasn’t concentrated. The largest 50 companies became known as the Nifty Fifty and were lauded for their ability to capture and maintain market share.

Dot-com Era (1983-2000): Microsoft controlled 97% of the PC market. The Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft and the FTC ruled against Intel.

iPhone Era (2009-Today): Apple has a 59% share of phone sales in America. Google has a 71% share of global phone operating systems and a 79% share of search. Facebook has 60% of all social media users. Tesla accounted for 80% of the EV market in 2019 and now accounts for 44% of the EV market. Amazon captures 38% of all online retail sales in America. Nvidia sells between 70% to 95% of all artificial intelligence chips.

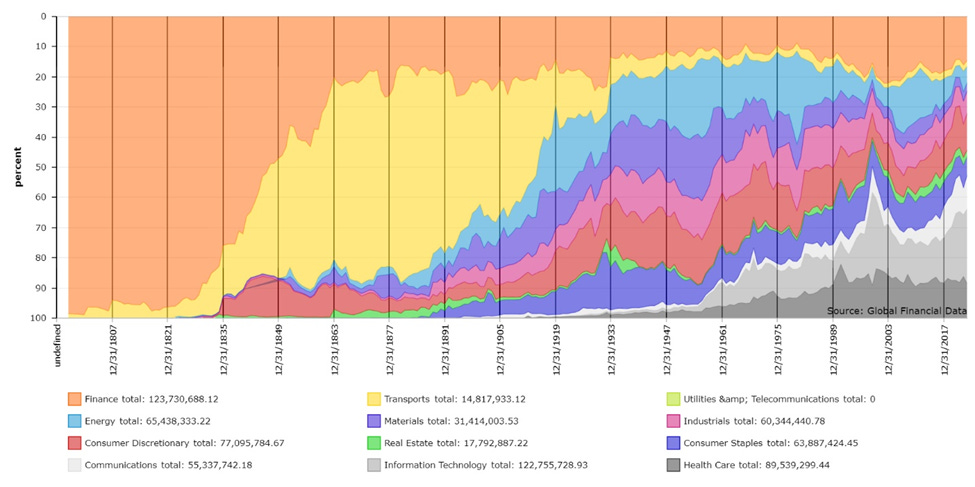

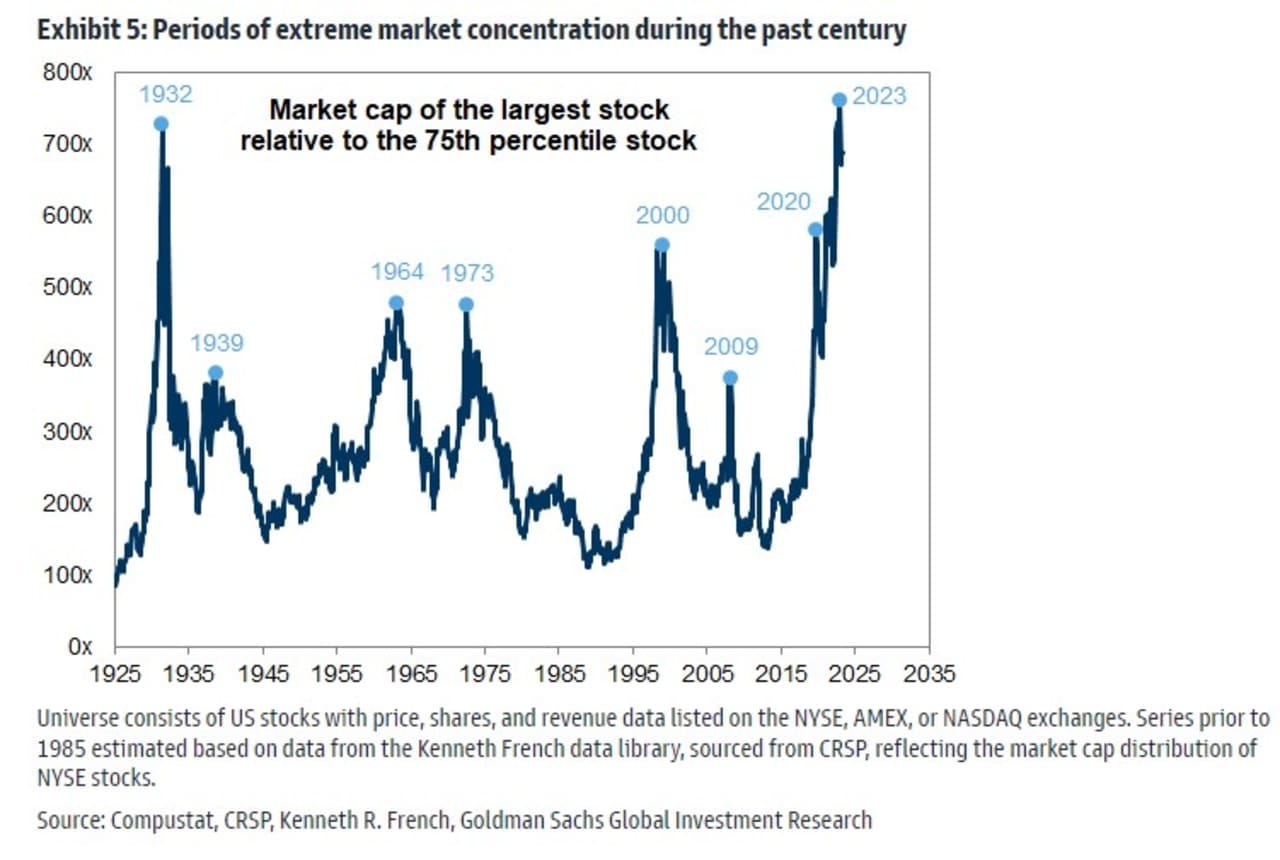

The potency of these monopolies can be roughly measured by taking the market cap of the 10 largest stocks as a percentage of the total stock market. A “normal” concentration is 22% across America’s financial history. Manias drive concentrations much higher.

Railway Mania (1840-1860): 16% (1840) → 31% (1860)

Gilded Age (1873-1906): 19% (1892) → 26% (1904)

Roaring Twenties (1920-1929): 15% (1920) → 24% (1932)

New Deal Era (1932-1940): 22% (1932) → 25% (1939)

Cold War Era (1949-1973): 20% (1949) → 29% (1973)

Dot-com Era (1983-2000): 17% (1988) → 27% (2000)

iPhone Era (2009-???): 17% (2014) → 33% (Today)

Here is another measurement of market concentration.

Declining Stock Yields

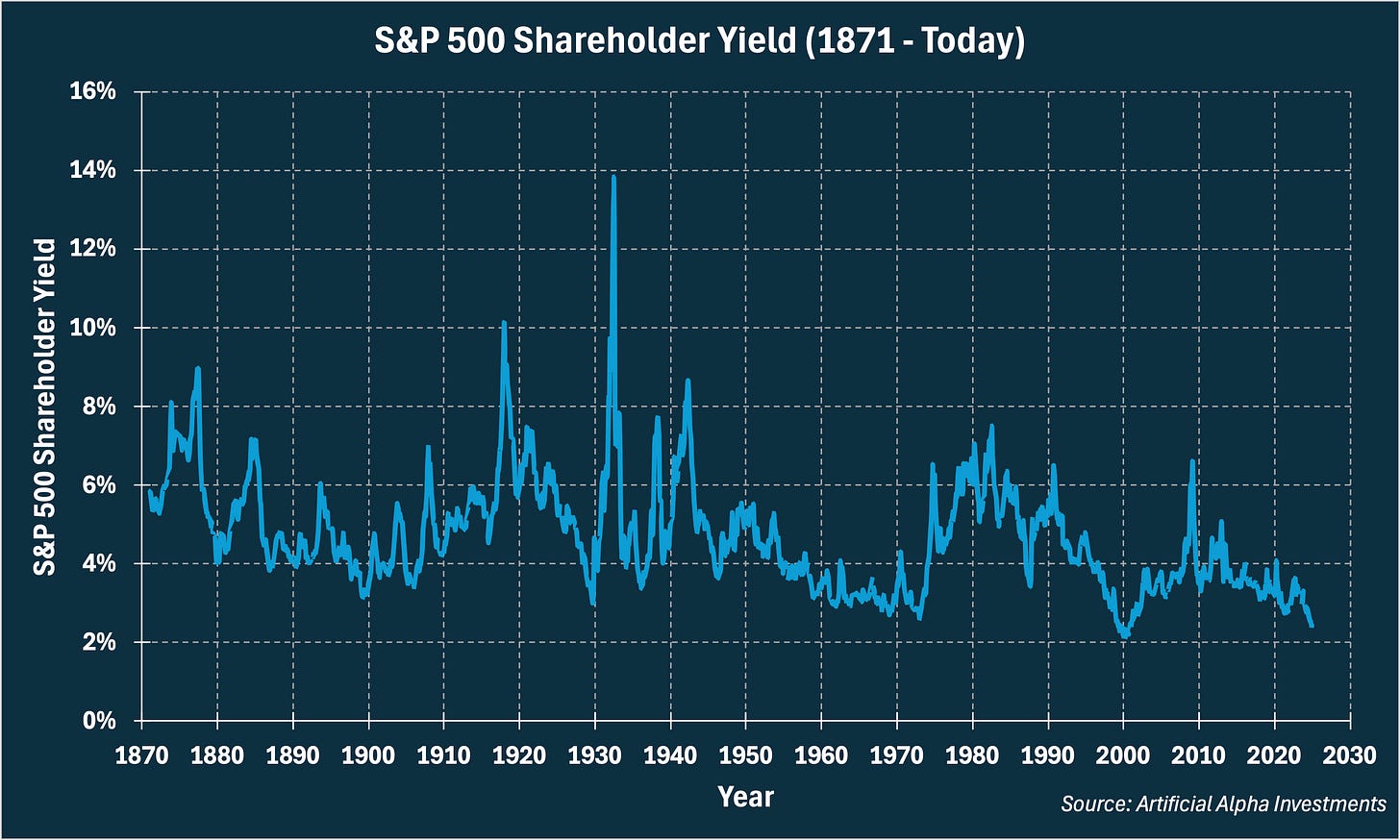

New technologies are unproven in the beginning, and it is unclear which businesses will win. Shareholders initially demand a high yield to match excessive risk.

By the end of each era, new technologies are widespread and shareholder payments seem predictable. Shareholders are willing to accept lower yields due to a perception of stability.

A “normal” Shareholder Yield in post-war America is 4.1%. Manias drive yields much lower.

Railway Mania (1840-1860): No Data

Gilded Age (1873-1906): 9.0% (1877) → 3.1% (1899)

Roaring Twenties (1920-1929): 7.5% (1920) → 3.0% (1929)

New Deal Era (1932-1940): 13.8% (1932) → 4.0% (1938)

Cold War Era (1949-1973): 5.6% (1949) → 2.6% (1972)

Dot-com Era (1983-2000): 7.5% (1982) → 2.1% (2000)

iPhone Era (2009-???): 6.6% (2009) → 2.4% (Today)

Fraud

Of all the “behavioral” indicators of a mania, I believe fraud fits into this framework the best. Most of all, because many of these frauds are adjacent to the latest technologies.

Railway Mania (1840-1860): The Credit Mobilier Scandal

Gilded Age (1873-1906): Green Goods Scams

Roaring Twenties (1920-1929): Ponzi Schemes

New Deal Era (1932-1940): Gold brick scams

Cold War Era (1949-1973): Various federal government and military coverups

Dot-com Era (1983-2000): Fake antivirus scams

iPhone Era (2009-???): Cryptocurrency Pump and Dumps

Political Instability and War

What’s fascinating and horrifying about these periods of technological change is that they all seem to end with war. Wars that are often waged and won using the latest innovation. I’m not totally sure what to make of this correlation, but I think we see markers of it today.

Only one major U.S. war (the Korean War in 1950) escalated during more moderate stock market concentration and/or yields.

Railway Mania (1840-1860): Civil War (1861-1865)

Gilded Age (1873-1906): Philippine–American War (1899-1902) and WW1 (1914-1918)

Roaring Twenties (1920-1929): Smoot–Hawley Tariffs (1930-1934)

New Deal Era (1932-1940): WW2 (1939-1945)

Cold War Era (1949-1973): Vietnam War (1964-1973)

Dot-com Era (1983-2000): Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (2001-2011)

iPhone Era (2009-???): Drone, AI, and Trade Wars

Reorganization of Capital

Back to finance. These manias also tend to end with increased competition for capital. Giants eventually fall. Capital flows to their competitors. Below are the annualized total returns for large-caps, mid-caps, and small-caps in the 5 years following each era.

Railway Mania (1840-1860): No Data

Gilded Age (1873-1906): No Data

Roaring Twenties (1920-1929):

S&P 500 (1931-1936): 9.1%

Mid-Caps (1931-1936): 19.9%

Small-Caps (1931-1936): 27.1%

New Deal Era (1932-1940):

S&P 500 (1939-1944): 9.3%

Mid-Caps (1939-1944): 20.2%

Small-Caps (1939-1944): 30.3%

Cold War Era (1949-1973):

S&P 500 (1974-1979): 8.4%

Mid-Caps (1974-1979): 21.3%

Small-Caps (1974-1979): 27.8%

Dot-com Era (1983-2000):

S&P 500 (1999-2004): -1.2%

Mid-Caps (1999-2004): 10.6%

Small-Caps (1999-2004): 19.7%

iPhone Era (2009-???): No Data

The S&P 500 averaged 6.4% across the small sample, which isn’t catastrophic but probably more trouble than the volatility of those periods was worth. Mid-caps and Small-caps averaged 18.0% and 26.2% respectively, as they finally enjoyed the benefits of the new technology.

Benefits of Diversification

Through both qualitative and quantitative comparisons, I might suggest we are experiencing a financial mania. It is unclear to me how long this environment will last, how low stock yields will fall, or how concentrated the market will grow. Conversely, I also can’t be sure that an especially painful period will follow close behind (although, all of these eras did end with painful market drawdowns).

Historically speaking, diversification has been directionally correct in this type of environment. I know stocks best, so I might suggest mid-caps and small-caps, but other investments are suddenly competitive too. Treasuries have yields again, TIPs have real yields, and gold has outpaced the S&P 500 since Q1 2021.

The right type of diversification is person-specific and situation-dependent. Please have a conversation with a professional first if you feel a need for diversification!

My Own Reaction

I manually rebalanced my investments recently so that my top 10 holdings make up 22% of my portfolio. Specifically, I sold S&P 500 ETFs in tax-deferred accounts and bought mid-caps and small-caps over the past 7 months. I hope to do more.

I don't trade factors for me or my clients in taxable accounts, because it's more trouble than it's worth, but I'm prepared to change my stance on that given the potential opportunity in front of us.

Paying down more mortgage principal with my savings is in the cards too.

All in all, let’s not treat “diversification” with disdain in 2025. It might be right for plenty of investors.