The 4% Rule

Part 1 of the Diversification Pillars series

Rules of thumb act as my north star in finance, especially those that form a foundation for further optimization. This will become a series that substantiates those guidelines and then ventures down various paths of optimization.

As the title suggests, this letter will introduce the 4% rule first (Cooley et al., 1998). I think the 4% rule is most core to retirement planning because it acts as a prescription for both retirement saving and retirement spending.

The 4% rule proposes one withdraw 4% of their savings in year 1 of retirement and increase that withdrawal by the rate of inflation in subsequent years. This simple prescription intends to maximize withdrawals and provide lifestyle consistency, while keeping failure rates to a minimum.

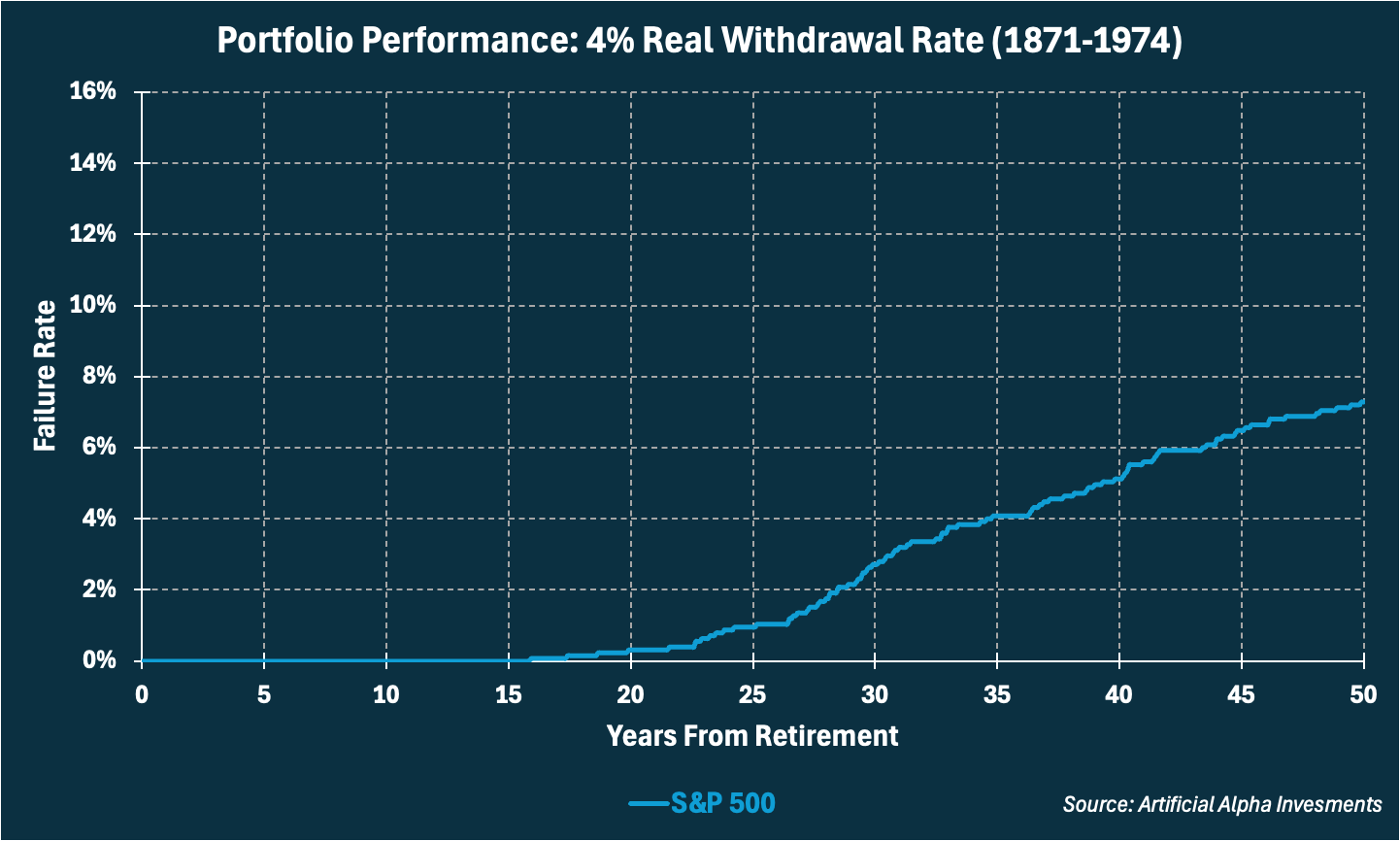

The 4% rule relies on historical data and backtesting for substantiation. As far as I know, useful academic data on core asset prices begin in 1871 (Shiller, 2000). These data, which span more time than even the original study, allow us to test the success rate of 1,248 monthly retirees between 1871 and 1974.

Our dataset includes dozens of recessions with different peculiarities and pitfalls. How often did the 4% rule fail our ancestors?

My research found very similar results to the original study. Holding the S&P 500 and following the 4% rule failed our retirees 1% of the time within 25 years and 4% of the time within 35 years. These are decent results for a rule of thumb.

But I know there is more we can do to improve these outcomes. I will head down that path of optimization in the next letter by invoking the 60/40 rule and exploring the benefits of diversification.